Life is full of painful lessons, but some people are slow to learn. This statement is epitomized in the story of an old driller one of us met early in our career as a geologist. The driller was a very talented and hard-working guy who had several fingers missing on both hands. When asked how he lost his fingers he told the story of how in his 30’s he was a quarry manager and would walk around the crushing plant with a detonator in his pocket. During quiet periods in the day, he pulled the detonator out and would tap the explosive charge on a piece of metal, such as a handrail. Then one day, “unexpectedly”, the detonator exploded and he lost 2.5 fingers on his right hand. After a stay in hospital and several weeks off work, he returned to work where, 6 months later, he did exactly the same thing to his left hand.

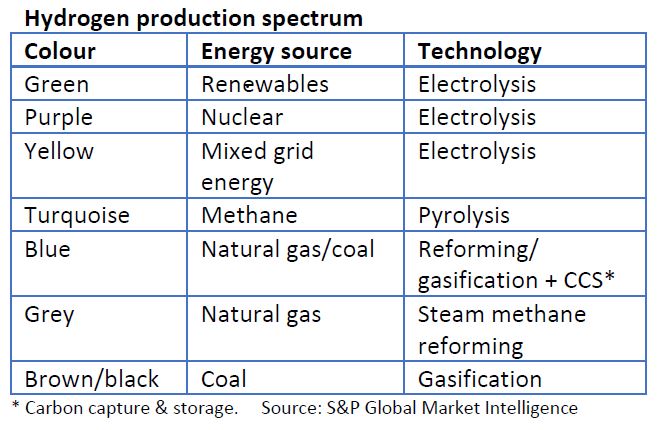

Hydrogen is the hot topic for 2021, but the question we’re asking at Acorn Capital is whether it’s a great investment opportunity or, akin to the old driller with missing fingers, is it like playing with explosives….twice! The upside for hydrogen is clear. As governments around the world are setting tougher and tougher emissions targets, low- and zero-carbon fuels, such as hydrogen, are being touted as a core part of the future energy mix. But on the flip side, the hydrogen market is currently miniscule, manufacturing costs are high and the variants for its production seem to cover every colour in the rainbow (e.g., green, blue, grey and more). For our final issue of Market Insights in 2021 we present an overview of hydrogen, discuss the challenges and opportunities, and provide insights into how we view the opportunities for investors.

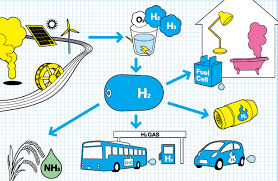

There are four key features of hydrogen that are important for its future applications. Firstly, hydrogen is a rich source of energy that can be burnt or combined with oxygen in a chemical reaction to generate electricity and heat. This means it can be used in the production of fuel cells. Secondly, the only by-product of burning hydrogen or using it to generate electricity and heat is the production of water (H2O). Thirdly, hydrogen is a strong reducing agent so may also be used in a range of industrial processes, including steel production where it could one day replace coking coal. And finally, hydrogen is incredibly abundant and there are many different methods of production.

While a range of colours are commonly used to describe the many ways of producing hydrogen, it is simpler to divide them into two categories. Green hydrogen is produced from water (H2O) using electrolysers powered by renewable energy. This is the process that Twiggy Forrest has championed. All the other forms are produced from fossil fuels with resulting carbon emissions that may (or may not) be captured and either sequestered or used. Today, the majority of the world’s hydrogen is produced from natural gas using steam methane reformation (i.e., grey hydrogen). This involves the separation of hydrogen and carbon atoms from the methane (i.e., CH4).

Green hydrogen is not a new technology, but it is yet to be produced at a commercial scale or with an efficiency and price that makes it competitive with other forms of energy. On the positive side, costs are falling as the efficiency of electrolysers improve and renewable energy becomes cheaper and more widely available. Also, the equipment using hydrogen fuel cells (e.g., hydrogen-powered trucks) are becoming more efficient and regulatory pressure to adopt low- or zero-carbon energy is fast-tracking research and development into the space. However, the widespread adoption of hydrogen, whether it be green, blue, grey or any another colour, faces numerous challenges. For instance, hydrogen gas is highly flammable, has very low density, requires ultra-low temperatures to keep it liquid and has a propensity to leak and to weaken metal or polyethylene pipes. This makes storage and long-distance transportation less efficient than for liquified natural gas (e.g., gas in Queensland can be piped at moderate cost to Sydney and Melbourne). One solution is converting the gas into ammonia (i.e., NH4), but this creates additional costs and different challenges for transportation.

Despite these issues, there has been enormous momentum in the hydrogen sector in 2021, especially at the junior end of the market. But 2022 will be a different year, so where should investors be looking and how do they assess the opportunities? We think the first thing to do is to stand back and assess the sector as a whole. Green hydrogen may be a great long-term goal, but blue hydrogen could be an important and commercially viable stepping-stone for the sector. The advantage of blue hydrogen is it would take the commercially viable process used today for grey hydrogen and simply add carbon capture and storage to store the emissions. This has its challenges, but if it were to work then contrary to current market sentiment it is the large energy companies who are best positioned. Their advantages include deep in-house chemical expertise, operational skills in carbon capture and storage, and most importantly of all, access to large industrial sites adjacent to ports for manufacturing and distribution.

For green hydrogen, the opportunities are greater but the risks are much higher. Fortunately, strong attention from governments industry and investors is driving the innovation that is desperately needed in the sector. A key starting point for this innovation is the need to improve the cost and efficiency of electrolysers. For electrolyers that use the alkaline process, the equipment is reasonably cheap to manufacture but the products are highly corrosive and the plant is expensive to maintain. In contrast, the proton exchange membrane (PEM) process is non-corrosive but expensive to manufacture. New variants of both processes are being developed, but none have been proven on a commercial scale. On top of these challenges, scale-up is likely to be very slow. FMG modified a dump truck to operate on green hydrogen, but it only ran for 20 minutes. Therefore, the initial application of green hydrogen will probably be very limited and small in scale. It will scale-up, but this will take time.

The final perspective we want to discuss on hydrogen is industry’s history at adopting new technologies. When you look back at the adoption of major new technologies in the resources and energy sectors, such as High Pressure Acid Leach (HPAL) and bio-oxidation, the early movers were rarely the biggest winners. For example, Andrew Forrest’s Anaconda collapsed following a multitude of start-up issues with its HPAL plant, yet Glencore is successfully running the operation today. Bio-oxidation also had a decade or more of trouble before being properly understood and successfully adopted. The risk for hydrogen (whatever its colour) is that the rush to be an early mover will create some major casualties. This does not mean the NextGen Resources Fund will never invest in the sector. Instead, unlike the driller with missing fingers, we will consider the risks when playing with something very explosive.